42 years ago, when A Rocha was founded, scientists viewed geology as the bedrock, so to speak, of an ecosystem, which would determine the soil type and therefore the plants, insects and other species that could live there. Now, our understanding is flipped: it’s a few keystone species which are vital to the survival of other species in the ecosystem. When you remove a keystone species, the entire arch of life beneath it collapses.

Apex predators often play this role by determining how nutrients are cycled through the rest of the food chain. The Blacktip Reef Shark Archarhinus melanopterus studied by A Rocha Kenya feeds on a variety of smaller fish populations, which protects Watamu’s reef ecosystems from overgrazing. A Rocha USA has observed a similar impact of the American Alligator Alligator mississippiensis in Florida’s Indian River Lagoon. Aside from being a top predator, they create holes and trails which retain water during the dry season, providing habitat for fish and food for wading birds. Several other reptiles even use abandoned alligator nests as their own.

Not all keystone species are predators, or even animals! A Rocha Ghana is restoring Keta Lagoon Complex Ramsar Site by planting mangroves. These powerful trees support hundreds of species by providing habitat for fish and crustaceans, nesting spots for bats and birds, and food for mammals. They benefit humans as well, by providing coastal communities with food, livelihoods and protection from extreme weather events.

In India’s Bannerghatta-Hosur Landscape Asian Elephants are known as ‘ecosystem engineers’ who modify the landscape over a vast range, benefiting and impacting an array of species. While roaming the forest, they trample trees which creates open woodlands where grasses can grow. This provides essential food for a variety of grazing herbivores, as well as habitat in the damaged trees for lizards and other creatures. They also disperse seeds and cycle nutrients in their dung. Even their pad marks (footprints) can function as microhabitats, as the depressions they create accumulate water and subsequently support transient populations of insects.

On the other hand, some very small species have a massive impact, like the Pacific Salmon cared for by A Rocha Canada. In their epic journey from freshwater to the ocean and back, these salmon feed life wherever they go. They provide essential nutrients to bears, wolves, eagles, killer whales, insects and even the soil itself. Scientists have discovered that the trees within 30 meters from a salmon bearing stream have larger growth rings in good salmon years and are healthier than trees further into the forest!

There’s much we can learn from these creatures which benefit their neighbours. In Genesis 1:26-28, God made humankind in his image and likeness and made us responsible for all the other creatures, making us the ultimate keystone species. Sadly, many of the environmental problems we face are due to humans’ misuse of our ‘dominion’ over other creatures. In its biblical context, ‘dominion’ does not mean domination but servant leadership. Keystone species teach us that restoring right relationships between humans, God and the rest of creation is what’s needed to begin healing the environment.

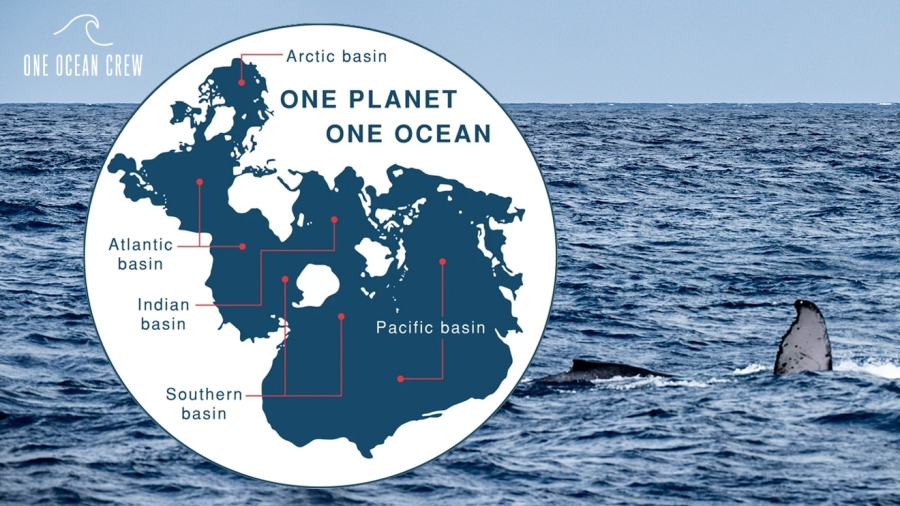

The conference sparked progress – including further support for the Pelagos Sanctuary, near me in the Mediterranean. Support for a global plastics treaty grew to over 90 countries, and 37 countries now support a moratorium on seabed mining (up from none in 2022). A treaty on the governance of the high seas – 50% of the planet and currently without governance – jumped from 30 to 51 ratifications. That’s nine short of the number needed, but there is hope ratification will be achieved this autumn, to come into force in January 2026.

The conference sparked progress – including further support for the Pelagos Sanctuary, near me in the Mediterranean. Support for a global plastics treaty grew to over 90 countries, and 37 countries now support a moratorium on seabed mining (up from none in 2022). A treaty on the governance of the high seas – 50% of the planet and currently without governance – jumped from 30 to 51 ratifications. That’s nine short of the number needed, but there is hope ratification will be achieved this autumn, to come into force in January 2026.